The commencement of winter quarter has brought along the second Humanities Core lecture series—this time, connected to the Inca Empire in the Andes, those who they have conquered, and those who they have been conquered by.

“Conquest and colonialism is a story that the conquerors tell themselves”

Diving into the material with Professor Rachel O’ Toole during our first lecture together, a series of interesting points were brought up regarding colonization and storytelling.

Even within the first lecture, I was able to grasp a lot of information regarding the Incan Empire and the many misinterpretations that have been built on their existence. The forms of domination that had taken place and the power dynamics within the Andeans, Incas, and Spaniards have been illustrated under different perspectives depending on the story teller.

The way in which stories are told usually caters to the writers of the story. The conquers are those who usually have the first say and give the first insight about the events that have taken place. Like a race, there is a constant struggle that occurs, with people rushing to the finish line, attempting to push their idea of truth out the quickest.

This in turn impacts the “truth” value of the story and the credibility of their statements. In the case of the Inca Empire, the Spaniards were able to paint this image regarding the conquest, giving justification for their actions and reaching the public first. It is extremely interesting to see the timestamps and publication dates for different articles and their writers. Those who are conquered are usually silenced until no end, unable to speak out about the incident—leaving the conquerors to create their own rendition of what they believe to be true.

Going over the lecture slides with Professor O’Toole, we went over the different methods of history, which were interesting to analyze and understand the backstory of. For instance, the distinctions made have helped to develop an understanding the power dynamic running through historical events.

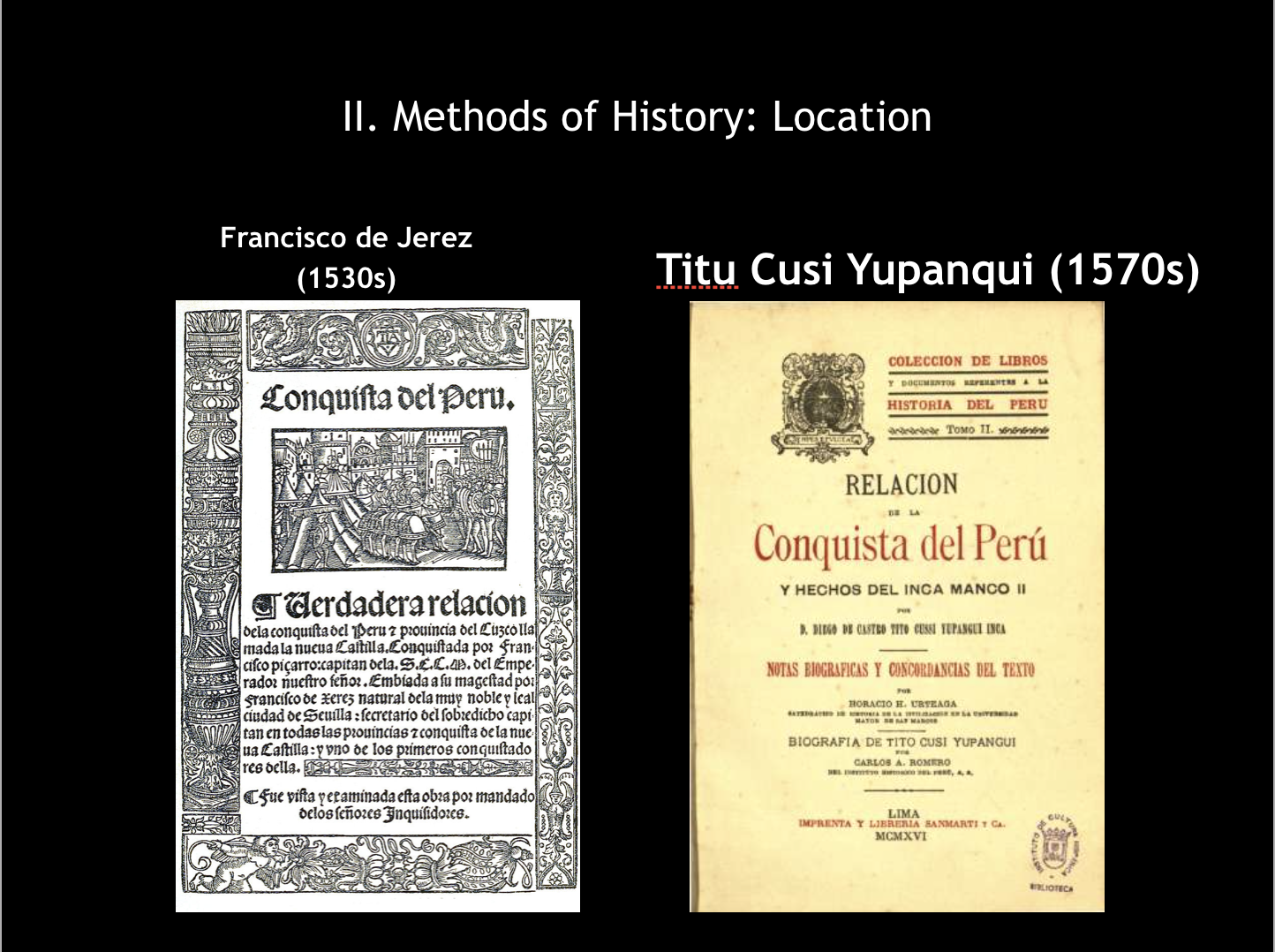

Francisco de Jerez, Francisco Pizarro’s secretary and notary, was able to publish his rendition of the conquest, True Account of the Conquest of Peru, in the 1530s. Written shortly after the capture of the Inca Atahualpa at Cajamarca, the work became the most influential of the early accounts of the conquest of the Andean region. The work is told from Jerez’s perspective, normalizing the conquest and, ultimately, giving a laundry list of what he sees and his experience.

On the other hand, Titu Cusi Yupanqui’s story, An Inca Account of the Conquest of Peru, was not uncovered until the 1570s, which is problematic, for Jerez’s story had enough time to reach the public and spread this unrealistic sense of “truth”. Yupanqui’s story comes from a different angle, giving a more graphic and hard hitting approach to the history. The account addresses the struggles that multiple generations in his family underwent due to the conquest of the Inca Empire and how detrimental had been.

Its Connection To Conquest

Recognizing that the retrieval and recasting of information is most evidently available by those who have control is an important step to take on when looking at this topic. Moreover, the context of one’s story and motives are ways to filter through false rewritings and portrayals of instances.

This issue continues to be projected in the modern society. Through the media, facts and stories are often twisted to “clickbait” readers—with little attention and care to whether or not it is the actual truth.

The misconceptions previously brought up during older forms of communication have been heightened with the new wave of technology in the modern day. Thus, this change has made it extremely easy to become blindsided and moved by biases: which continue to flood our newsfeed on a daily basis. Moreover, it becomes a bloodbath with who is able to reach the public quicker with their own sense of right, which is extremely dangerous in instances where people may be painted and recognized in a certain light that is not optimal.

With constant access to technology at our finger tips, information has become extremely accessible. It is easy to get sucked into the world of media and forget to address the credibility of a source before sinking it in as the full truth.

I liked your analogy comparing the production of information and “truth” to a race. However, building on how this pertains to today’s technology, why is it that some newly produced information is more quickly accepted than others? For example, people are really quick to jump on bandwagons endorsed by celebrities, so does the person/group producing the information matter more than how fast it is made public?

LikeLike

The concept covered in your post is extremely interesting because, like you said, it used to be that the colonizer’s perspective of an event was the only one available to the people. I actually think before technology, it was much easier to promote and establish one idea as the truth as there was very little way to dispute the accepted beliefs. In today’s society, people have access to many sources that allow them to form their own opinion and thoughts about issues or events.

LikeLike

I really liked your statement that history was written by and for the ‘winners’. The comparison of this to clickbait was very unique and I had not thought about this connection before. I also believe that clickbait plays a huge role on the public and heavily impacts our beliefs as a direct result. Although technology makes it easier to connect and communicate with people, it can be dangerous in that it is often biased and based on what will get the most views rather than the truth.

LikeLike